Eugene D. Genovese. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Pantheon, 1974.

Eugene D. Genovese. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Pantheon, 1974.

Writing a book review like this is usually a pretty easy exercise for me – it’s normally just a matter of organizing my thoughts, writing them down, and some proofreading (although I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t always do this last step as carefully as I should). Many of the books on my reading list are very important historiographic achievements – Gordon Wood, Glenda Gilmore, Edmund Morgan, Bernard Bailyn, Jon Butler, and Edward Ayers are big names in the world of history. Despite their formidable reputations, I feel very comfortable reading their books and sharing my sometimes critical thoughts with you on the Internet. With the possible exception of The Structures of Everyday Life by the great Ferdinand Braudel, no other book on my reading list has left quite the impression on historians, the Academy at large, and the educated public as Eugene D. Genovese’s masterful Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. This is one of the most transcendent history books ever written – it is now 37 years old and in 50 more, people will still be reading, talking about, and finding intellectual and emotional inspiration in the pages of Roll, Jordan, Roll. And so you might understand why the idea of reviewing this book and putting said review on the Internet, to be frank, scares the hell out of me. What can I possibly add to the discussion of this great book that hasn’t already been said more profoundly and more eloquently by somebody with more talent that me? Not to mention that, like many of my colleagues, I have very conflicted views about Genovese because of the ideological turns he has taken during the latter stages of his career. But I can take comfort in the fact that I’ve tried and failed at things that matter more than a simple book review (i. e., marriage), so the stakes aren’t exactly high. With these reservations in mind, here goes nothing…

Roll, Jordan, Roll is the most important Marxist interpretation of American slavery. At the time he wrote this book, Genovese was a committed communist, and if this bothers you, I strongly urge you not to let this put you off if you are considering reading it. Marxists view the world in terms of class conflict and historical models first put forth by Karl Marx. While many individuals, particularly Americans, find socialists and socialism extremely distasteful, the rich history of the poor and oppressed is unimaginable if not for the influence of Marxist historians. Furthermore, much like English labor historian E. P. Thompson, Genovese adds a humanist element to his studies of American slaves and slaveholders. Rather than forcing his subjects to become soulless statistics, Genovese portrays slaves and masters with a sensitive humanity. That is my favorite feature of this book. Through reading Roll, Jordan, Roll, it is possible see both slaves and owners as good-hearted humans. It is a self-evident truth that life is inevitably about interpersonal relationships. Any particular slave and any particular owner were on opposite ends of the social hierarchy and it is tempting for modern observers to simply assume that they naturally hated each other. But human nature dictates that if you put two people together, despite whatever vast differences they have, they might end up liking each other and developing warm feelings. So it was many times with masters and slaves in the antebellum South. No historian is going to deny that the system of American slavery was degrading, brutal, and exploitative. But humans, both and good and bad, white and black, operated in the system of American slavery. And it’s the human element that Genovese understands better than any other scholar I’ve ever read and he illuminates human behavior within a particular historical paradigm.

For Genovese, paternalism and the master-slave relationship, with their imbedded reciprocal duties, defined antebellum southern society. Paternalism did not emerge out of white altruism toward blacks, but rather “out of the necessity to discipline and morally justify a system of exploitation.” Paternalism meant vastly different things to the owners and the slaves, but it humanized slavery. “For the slaveholders paternalism represented an attempt to overcome the fundamental contradiction in slavery: the impossibility of the slaves’ ever becoming the things they were supposed to be. Paternalism defined the involuntary labor of the slaves as a legitimate return to their masters for protection and direction. But, the masters’ need to see their slaves as acquiescent human beings constituted a moral victory for the slaves themselves. Paternalism’s insistence upon mutual obligations – duties, responsibilities, and ultimately even rights – implicitly recognized the slaves’ humanity.” Ultimately, paternalism allowed the slaves to have a critically important role in shaping southern society and southern culture. It also had serious consequences in regards to black solidarity, “Paternalism created a tendency for the slaves to identify with a particular community through identification with its master; it reduced the possibilities for the identification with each other as a class. Racism undermined the slaves’ sense of worth as black people and reinforced their dependence on white masters. But these were tendencies, not absolute laws, and the slaves forged weapons of defense, the most important of which was a religion that taught them to love and value each other, to take a critical view of their masters, and to reject ideological rationales for their own enslavement.” Thus, by accepting paternalism, blacks legitimized the social order but also found cultural strength to resist the cruel mix of racial and class oppression. Genovese’s book is about how the social order operated and how the slaves thus used their human nature to shape a system that made life livable, even if it had grave consequences. Roll, Jordan, Roll is atypical in the sense that it does not unfold like most historical monographs with an introduction that lays out a carefully worded argument and then crafts a narrative to support said argument. In the fashion of social historians of the 1970s, Genovese starts with the theory outlined above and then uses it as a lens to understand practically all aspects of slave life – thus the book’s magisterial sweep and sometimes encyclopedic feel. There is a lot of information interpreted through this Marxist framework and Genovese set much of the historiographic agenda on slavery for decades to follow. It still holds tremendous weight today.

Beyond the well-known history of Marxism in the 20th century, some additional background might be instructive in order to fully understand the historiographic importance of Roll, Jordan, Roll. Genovese found that religion, above all else, allowed the slaves to develop a strong sense of personal worth in that “it proclaimed the freedom and inviolability of the human soul.” The slaves’ own unique version of Christianity “drove deeper into his soul an awareness of the moral limits of submission, for it placed the master above his own master and thereby dissolved the moral and ideological ground on which the very principle of absolute human lordship must rest.” In the Christianity that emerged in the slave quarters, the personas of Jesus and Moses merged. Genovese writes that “Moses had become Jesus, and Jesus, Moses; and with their union the two aspects of the slaves’ religious quest – collective deliverance as a people and redemption from their terrible personal sufferings – had become one through the mediation of that imaginative power so beautifully manifested in the spirituals.” While this merging muted any politically revolutionary implications found in scripture, slave religion “fired them with a sense of their own worth before God and man. It enabled them to prove to themselves, and to a world that never ceased to need reminding, that no man’s will can become that of another unless he himself wills it – that the ideal of slavery cannot be realized, no matter how badly the body is broken and the spirit tormented.” Genovese also asked how African cultural survivals in North America manifested themselves in the slaves’ religious experience. Among the most interesting was the rejection of the doctrine of original sin “because black theology largely ignored the one doctrine that might have reconciled the slaves to their bondage on a spiritual plane.” African religion does not have any equivalent to original sin – with its inherent guilt, self-hatred, and pessimism – and so black religion in America, like its African antecedent, embodied joy and rejected guilt.

The delicious irony of a committed Marxist saying anything so moving about religion notwithstanding, Genovese’s lengthy discourse on religion was a watershed in American religious historiography. Few historians of any ideological bent had even studied southern religion at all, but things were changing. The 1970s was a dramatic decade in the field of southern religious history. Prior to this decade, studies of southern religion were usually self-indulgent and celebratory studies produced by religious denominations for their own glory and to give parishioners a warm feeling in their hearts. There was very little in these histories to encourage critical thinking or reflection beyond religious platitudes. Scholars like John Boles, Donald Mathews, Samuel Hill, and Genovese brought forth a profusion of research that set a very high standard for all subsequent scholarship. While Genovese’s book is one of the most important books every written on American slavery, it’s chapters on religion remain some of the most important ever written on black religion. There has been an impressive amount of scholarship on southern religion over the past 40 years and all of it is influenced in some way or another by Roll, Jordan, Roll. It is easy for graduate students or professors who are not specialists in religion to fail to give Genovese the proper credit he deserves in pushing forward a research agenda in the study of antebellum southern religion because this book is simply so massive and encompassing. I would further suggest that other subfields of southern history owe a similar debt to Genovese. There are early indications of in the pages of this book of the field that eventually matured into gender history, twenty years before the blossoming of a historiographic juggernaut. There are other historical books that cast such a large shadow, but I know of few that anticipate major historiographic shifts in quite the manner of Roll, Jordan, Roll.

Beyond the obvious fact that Genovese’s book was influential and thus inspired a later generation of historians, I feel that one reason that it anticipates changes like the development of gender history or material culture analysis is Genovese’s tendency for interdisciplinary study. The 1970s was a golden age for what was then termed the “new social history.” Rather than producing books with theses designed to be more or less definitive (for lack of a better description), the new social historians used quantitative methods, applied theories from other disciplines, and rigorously followed the scientific method. Like their counterparts in science, new social historians presented their findings of research on a specific topic. The idea was that other historians would present findings that might corroborate or even contradict other findings. Eventually, however, a picture of the past would gradually emerge. Genovese’s book emerged in this milieu and while Roll, Jordan, Roll never distinguished (or subsequently dated) itself as “new social history” in the way that other studies did, Genovese’s free use of theory from other academic disciplines such as philosophy, anthropology and sociology was a noticeable trend in the 1970s. Young historians of the 1960s and 1970s who were looking for something new and exciting found much to be enthralled by in Genovese’s work. For example, following the example of sociologists who sought to understand the nature of society on global scale, Genovese made arguments about paternalism, laboring people, and power in a global context. We learn that the material condition of the slaves was usually not worse and sometimes better than English or northern factory workers. And they often fared much better than, say, Russian serfs or the Chinese who worked in the rice fields. While I am often skeptical that we can draw too many parallels across oceans, these sorts of comparisons are illuminating and are useful to understand the white slaveholders’ defense of their own regime and also to understand what the life of the laboring classes was like in a global context. Moreover, the text is peppered with quotations by the likes of Max Weber, Friedrich Nietzsche, Antonio Gramsci, and, for the coup dê grace, T. S. Eliot. Although things were changing, for a field that had traditionally been confined to the history of economic institutions, politics, and dead white men, the idea of drawing off thinkers like Nietzsche and Eliot in order to understand the poor and the oppressed in history was quite liberating. Genovese was highly influential but he did not inaugurate a new interdisciplinary paradigm. He was, however, hot on the scene during a time of dramatic historiographic ruptures and this highly influential book is a big indicator of much of the cutting-edge research, based on theory from other fields, that fully blossomed in the 1980s and 1990s and ushered in such quandaries as the postmodern challenge – but that’s another topic for another day.

For all of my praise, let me be clear that Roll, Jordan, Roll is far from perfect. The book is based on voluminous research and sometimes it is unclear exactly where Genovese is pulling his information from. The author thoroughly examined every plantation record he could get his hands on and through this research he become an unquestioned expert on slavery. All historians should hope to gain such expertise, but something about Genovese’s tone seems coercive – the author expects us to revere his knowledge of history and this is a wonderful way to deflect criticism. While overall, I buy most of what Genovese is selling, when I was reading the section on racial mixing I wanted to jump out of my skin. It has often been assumed by that many African Americans today have a great deal of European blood and, moreover, most historians believed that much of this racial mixing occurred before the Civil War because various laws instituted in the decades after Appomattox hindered interracial sexual intercourse. Genovese, however, pointedly argued that, at least on plantations, miscegenation was rare. He claims that “[p]robably, little more than 10 percent of the slave population had white ancestry.” Aside from the thorny word probably, this assertion raised my eyebrows because Genovese’s evidence is unreliable. Although today historians and other scholars have turned to DNA evidence to answer questions concerning African American genealogy, in the 1970s, Genovese was forced to rely on census records. Although the census is an extremely valuable historical resource, drawing these kinds of conclusions from the census is, at best, dangerous. And Genovese even concedes that other scholars have been right to be suspicious of census records because “mulattoes were so designated by the crudest observation” and moreover “that a tendency to underreport was manifest.” Determining racial origins of slaves (who might have had different skin tones based on their various African heritages) by either a cursory observation by a census taker or by the testimony of a master who usually had better things to do than answer questions from a nosey government agent is a dubious practice. While he acknowledges this problem, Genovese does not try to defend himself in a meaningful way (because he had no choice but to rely on the census figures – no other sources he had access to would even begin reveal a picture of the totality of interracial sex). He later goes onto to insist that one reason masters did not have more sex with their female slaves is that Victorian mores began to permeate the South, the assumption being that people started taking morality more seriously, an argument that I found to be completely unsubstantiated by any evidence presented by the author. Other scholars have cited common sexual liaisons between whites and blacks, and some recent DNA testing supports such claims. While his mastery of plantation records is dazzling, the chapter on miscegenation – the one chapter in the book that used evidence that I am personally very familiar with – left me wondering if there could have been other places where Genovese’s expert tone conveyed as much, if not more, than the evidence itself.

One of my former professors, Laura Cruz, once warned me that exceptional writing is a good way to hide your faults as a historian. If this is true, then Roll, Jordan, Roll would seem to be beyond criticism. This book is a historical and a literary achievement. Quite often, academic history is dense and boring. This book is dense yet engrossing and emotionally riveting. Genovese presents stories that are fascinating and educating in their details. For example, many people are natural leaders based simply on their personalities. While we often tend to think of leaders ending up as senators or CEOs, in the slave world such persons usually became a mammy or a driver. Rather than hiring a white overseer, some masters placed a great amount of trust in drivers – that is male slaves who supervised work in the fields or life in the quarters. “Capable drivers – and there were many such – readily became the most important slaves on the place and often knew more about management than did whites.” Not only did many masters respect such men, they often placed a great amount of trust in them – astonishing considering what we know about slavery. Consider the case of William S. Pettigrew, “an Episcopal priest who had to be away from his North Carolina plantation for months at a time, [who] despised white overseers and relied on two drivers, each of whom had charge of one of two adjoining plantations.” While these two slaves were illiterate, Pettigrew wrote letters to his drivers and sent them to a literate white neighbor who would periodically check in with the drivers and read them letters from their master. In effect, a man who had a great stake in the regime was placing almost total trust and thus his vast fortune in the hands of two men of a supposedly inferior race, a group that really couldn’t be trusted because they were considered to be naturally inclined to lie, cheat, and steal. The letters between the drivers and Pettigrew contained “lengthy discussions of crop conditions and plantation affairs that amply demonstrate the extent of the drivers’ knowledge and sense of responsibility.” While some drivers were indeed “sadistic monsters,” many were good and effective leaders. It might be tempting for some to think that these two slaves (named Henry and Moses) were sell-outs who did the white man’s bidding and forgot the needs of their people. But Genovese time and again reminds us that most people are not revolutionaries – that honor has been reserved for very few throughout history. These slaves were people who were just living their lives as best as they could and cream inevitably rose to the top and so slaves sometimes gained the trust of their masters. While the example of Pettigrew’s plantation might not be entirely typical, sometimes masters felt comfortable enough with their drivers and their ability to control the labor force to simply leave a plantation under black supervisor with practically no white oversight. If you ask me, that’s an amazing accomplishment, considering the class and racial assumptions of the day.

And if you wanted to know a slave with real power, you should have sought out a mammy. Genovese writes that,

Primarily, the Mammy raised the white children and ran the Big House either as the mistress’s executive officer or her de facto superior. Her power extended over black and white so long as she exercised restraint, and she was not to be crossed. She carried herself like a surrogate mistress – neatly attired, barking orders, conscious of her dignity, full of self-respect. She played the diplomat and settled the interminable disputes that arose among the house servants; when diplomacy failed, she resorted to her whip and restored order. She served a confidante to the children, the mistress, and even the master. She expected to be consulted on the love affairs and marriages of the white children and might even be consulted on the business affairs of the plantations. She presided over the dignity of the whole plantation and taught courtesies to the white children as well as to those black children destined to work in the Big House…In general, she gave the whites the perfect slave – a loyal, faithful, contented, efficient, conscientious member of the family who always knew her place; and she save the slaves a white-approved standard of black behavior. She also had to be a tough, worldly-wise, enormously resourceful woman; that is she had to develop all the strength of character not usually attributed to an Aunt Jane.

This is hardly a description of degraded women. In fact, this description sounds more like somebody with the savvy of an Oprah Winfrey rather than some stereotypical dutiful but dumb Aunt Jemima. But – and here is one of Genovese’s key points – the main reason slaves were not degraded as human beings was because the slaves who lived in this paternalistic paradigm did not allow themselves to be degraded. There is something in the human soul that demands respect from other people. And while the master could whip slaves into submission, this fire could not be extinguished by slavery.

Genovese reminds us that the evil of slavery cast a very long shadow on southern society. Genovese argued that slaves often did, in fact, have childhoods – that is a more or less lighthearted period of life before the reality of adulthood robbed individuals of their innocence. It made sense for masters to ease the young slaves into field work as a way to protect their investments. Usually, a child could expect to be sent to the fields between the ages of 12 and 14. By the time they reached 18, they would be working full days. As such, slave children away from the fields played games like all children will. But even for a young child who wasn’t being forced to work in the fields under the threat of the whip, the institution of slavery was omnipresent. Genovese wrote that “there was the game of playing auction. One child would play the auctioneer and pretend to sell the others to prospective buyers. They learned early in life that they had a price tag, and as children are wont to do, took pride in their prospective value.” When I read history books, I carry around a pencil with me and I underline important parts and make notes in the margins. When I saw read those two sentences, I wrote the only thing I could think of that emotionally summed up what I just read: “This is fucked up.”

Excuse my profanity, but sometimes nasty language conveys the painful rawness of reality better than more polite words. I read a lot of things in Roll, Jordan, Roll that infuriated me to think of the pitiful levels of self-deception humans will go through to justify what is clearly evil. But, as a person living in the 21st century, I was also continually astonished at how human the relationships that defined master and slave actually were because we tend to think of slavery as inherently inhuman. I was also surprised at how much agency the slaves exercised in creating southern society – Genovese’s subtitle suggest that the slaves, in effect, made the plantation world, even if they did not have cultural hegemony over whites. But Genovese captured something I’m not sure he realized. Everybody knows that children have a brutally honest quality that adults lack – simply put, they call ’em like they see ’em. Art Linkletter made a fortune on this premise. By mentioning that black children played auction, Genovese allowed the children, modeling the grown-up behavior they saw all around them, to tell modern readers the unbiased and raw truth often covered up by the fancy drapery of paternalism. You can humanize slavery with paternalism and warm master-slave relations all you want to, but once all the seductive paternalistic lies were stripped away and filtered through the eyes of honest children, slavery was like the game of playing auction. It was, simply and honestly, fucked up.

Fred Anderson. A People’s Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years’ War. Chapel Hill: The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

Fred Anderson. A People’s Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years’ War. Chapel Hill: The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

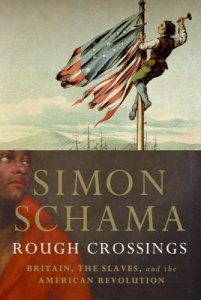

Simon Schama. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution. New York: Ecco, 2006.

Simon Schama. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution. New York: Ecco, 2006.